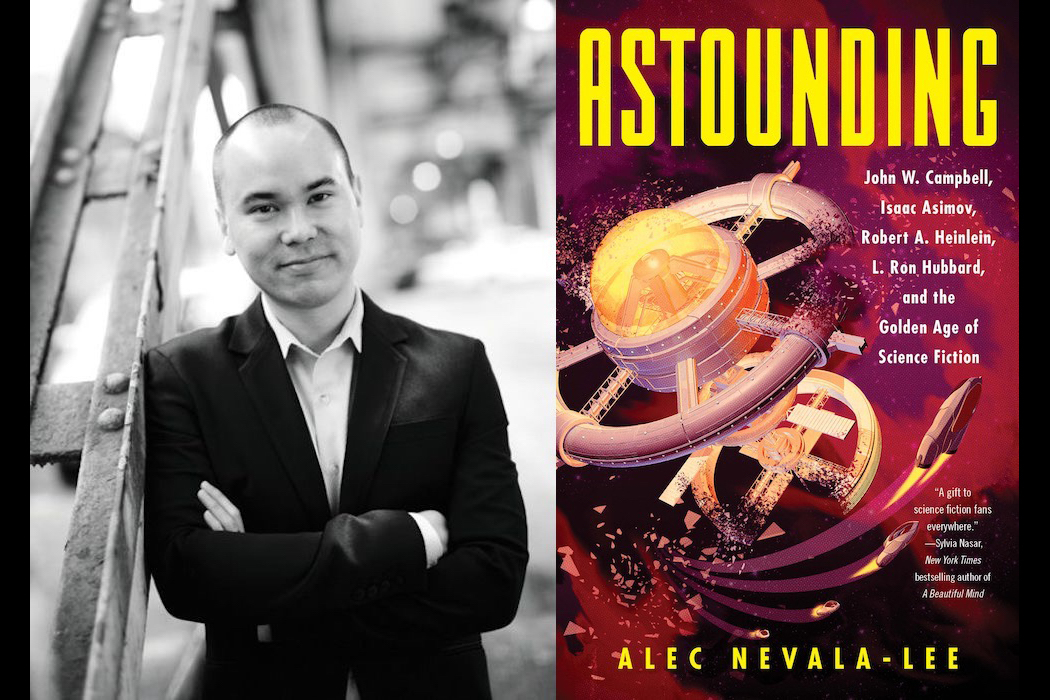

“Astounding” is author Alec Navala-Lee’s groundbreaking history of science fiction in America. Rather than give a cursory overview to the entire history of how stories published in pulp magazines transformed into an important literary genre, Nevala-Lee takes an in-depth look at “Astounding” magazine editor John W. Campbell and three of his most famous disciples: Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein and L. Ron Hubbard.

Campbell didn’t write many stories himself, instead assigning most of his best ideas to his writers at the magazine, although his brilliant novella “Who Goes There?” inspired the 1951 sci-fi movie classic “The Thing From Another World” and its 1982 and 2011 remakes as “The Thing.”

Asimov and Heinlein remain on the short list of science fiction’s greatest authors, while Hubbard mostly abandoned the genre after World War II when he developed that ideas that eventually led him to found Scientology as a religion.

Both Heinlein and Hubbard are Navy veterans and Asimov worked as a civilian researcher in support of the war effort. What happened during World War II plays a huge role in Nevala-Lee’s story and we’ve got an excerpt that details Heinlein and Asimov’s time working at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

Health issues prevented Heinlein from returning to active duty during the war and his wife Leslyn worked alongside him at the complex. Hubbard was pursuing a checkered Navy career that’s heavily detailed in “Astounding.”

Other characters mentioned in this excerpt include Asimov’s wife Gertrude, science fiction author Frederik Pohl, Lt. Cmdr. Buddy Scoles (assistant chief engineer for materials at the Navy Yard), science fiction author and fellow Navy Yard worker L. Sprague de Camp and Campbell’s daughter Peedee.

Selection from Chapter 7: A Cold Fury

During the war, one issue that was never far from anyone’s mind was the problem of rationing. Gertrude smoked, but neither she nor Asimov drank, and they became used to their friends asking if they had any extra liquor stamps. Their lack of interest in drinking was another quality that kept them socially apart. Asimov’s idea of indulging himself after moving to Philadelphia had been to consume a huge bottle of soda on his own, which only made him sick, and Gertrude wrote to Pohl, “Try as I may, propriety and dullness must be my lot.”

Another object of rationing was gas. The preferred mode of transportation at the Navy Yard was by bicycle, and Heinlein could often be seen pedaling between the buildings in his suit and tie. One day, as a joke, a coworker removed the tags from a few tea bags and stopped Heinlein in the hallway, offering to sell him some illicit gasoline stamps. After examining the paper slips, Heinlein handed them back coldly. “You’re lucky they weren’t real.”

He wasn’t inclined to make light of wartime sacrifices, and there were moments when the courtly mask that he cultivated so carefully seemed to crack. On his arrival at the Navy Yard, he had been assigned to the Altitude Chamber and Cold Room, which were used to test materials under conditions of low pressure and temperature. He supervised their construction before handing them over to de Camp, who was a lieutenant in the Naval Reserve. Heinlein was suffering from his usual medical problems—his back and kidneys were acting up—and he felt buried by paperwork.

Scoles, who admired his competence, assigned him additional administrative duties, which Heinlein accepted against his will. He wrote to Campbell, “I hate my job. There is plenty of important work being done here but I am not doing it. Instead I do the unimportant work in order that others with truly important things to do may not be bothered with it.”

He derisively called himself “the perfect private secretary,” but he was also good at it. Tension between civilians and officers often ran high, and Heinlein was respected by both groups, advising the inexperienced de Camp, who could irritate others, to “clip those beetling brows.” De Camp recalled, “It must have irked Heinlein to be working as a civilian while I, green to Navy ways, went about with pretty gold stripes on my sleeve. But he was a good sport about it, and I am sure his advice saved me from making a bigger ass of myself than I otherwise might have.”

Heinlein’s basic trouble—which Hubbard shared to an even greater degree—was that he was too imaginative to fully commit himself to the work that had to be done, even as he feared that they were losing the war. He learned to deal with it, but only by consciously willing himself into the attitude of patience that came naturally to Asimov. “A war requires subordination,” Heinlein wrote to Campbell, “and I take a bitter pride in subordinating myself.”

This remark was aimed directly at the editor. Months after their meeting with Scoles, Campbell’s status was still up in the air. Early on, he had been enthusiastic about the Navy Yard, writing to Robert Swisher that Scoles was recruiting science fiction writers “as the type of men wanted for real research today.” The editor added, “I have the satisfaction of already having succeeded in contributing a suggested line of attack that yielded results on one project.” He even reached out to del Rey about taking over the magazine in the event that he was drawn into war work.

Campbell remained unsure of his prospects for getting a reserve commission, however, citing a list of ailments, including bad vision in his left eye, a poorly healed appendectomy scar, an irregular heartbeat, and what he called “fear syndrome” in his psychiatric records. Ultimately, he didn’t even take the physical. His attempts to find a position at the National Defense Research Committee faltered—his contact was often out of town—and it became clear that his limited lab experience made him less desirable than the most recent crop of engineering graduates.

Heinlein told him that if money were an issue, he and Leslyn would be happy to contribute a stipend for Peedee, but he conceded, “Truthfully, we aren’t shorthanded enough to recommend it.” But he also advised:

I strongly recommend for your own present and futurepeace of mind and as an example to your associates that you find some volunteer work. . . . I predict that it will seem deadly dull, poorly organized, and largely useless. . . .I am faced with that impasse daily and it nearly drives me nuts.

He anticipated many of Campbell’s objections: “Remember, it does not have to be work that you want to do, nor work that you approve of. It suffices that it is work which established authority considers necessary to the war.” And he concluded pointedly, “But find yourself some work, John. Otherwise you will spend the rest of your life in self-justification.”

Campbell never did. He found it hard to subordinate himself to duties that didn’t utilize his talents, and he was disinclined to make the sacrifice that Heinlein had bitterly accepted. In the end, he decided to stay with his magazines, a civilian role with a high priority rating because of its perceived importance to morale. Heinlein never forgave him, speaking years later of “working my heart out and ruining my health during the war while he was publishing Astounding.”

The Heinleins still remained outwardly friendly toward the Campbells, as well as the de Camps, and they occasionally walked the two miles to visit Asimov and Gertrude. At work, their social life centered on the Navy Yard cafeteria, which was known without affection as Ulcer Gulch. Heinlein and Leslyn worked in different buildings—she had landed a job as a junior radio inspector— but they ate together every afternoon. Asimov became part of the lunch crowd when Gertrude left on a trip to clarify her immigration status, and after her return, Heinlein asked him to stay. Asimov resented the pressure, but finally consented “with poor grace.”

At the cafeteria, the food was terrible, and Asimov didn’t get along with Leslyn. She struck him as brittle and tense, and her constant smoking—she used her plate as an ashtray—soured him forever on cigarettes. Leslyn didn’t care for him, either. His years at the candy store had left him with the habit of devouring his food in silence, and when he popped half of a boiled egg in his mouth, she couldn’t contain her disgust: “Don’t do that. You turn my stomach.”

Asimov thought she was speaking to someone else. “Are you talking to me, Leslyn?”

When she confirmed that she was, he asked what he had done wrong—and swallowed the second half. She shrieked, “You did it again!”

His comments about the food grated on Heinlein, who decreed that anyone who complained had to contribute a nickel toward a war bond. Asimov knew that this was a message to him. “Well, then, suppose I figure out a way of complaining about the food that isn’t complaining. Will you call it off?”

After Heinlein said that he would Asimov tried to think of ways to get around it. One day, as he sawed through the haddock on his plate, he asked, in mock innocence, “Is there such a thing as tough fish?”

It was another battle of wills, and Heinlein wasn’t about to back down. “That will be five cents, Isaac.”

This time Asimov held his ground. “It’s only a point of information, Bob.”

“That will be five cents, Isaac,” Heinlein repeated. “The implication is clear.”

Asimov was saved when another employee, unaware of the rule, took a bite of ham and remarked, “Boy, this food is awful.” Rising to his feet, Asimov pronounced, “Gentlemen, I disagree with every word my friend here has said, but I will defend with my life his right to say it.” Heinlein dropped the system of fines. It was a victory, but a small one.

On September 25, 1943, the Soviets marched back into Smolensk. Two days later, a communiqué said that Petrovichi had been retaken after years under German rule. When Heinlein heard the news, he shook Asimov’s hand and congratulated him gravely. For the moment, at least, they were equals.

Word finally came of Leslyn’s family in the Philippines. Her sister, Keith, was interned with her two sons in Manila, but her brother-in-law, Mark Hubbard, had vanished. Until then, Leslyn had liked her job, but she began working so hard—”Just doing everything she could to shorten the misery of her sister,” a friend recalled—that it affected her health. She became the personnel manager for a machine shop with six hundred employees, and although she was suited for it—she was the only administrator who made a point of wearing the same uniform as the female workers— it caused her to drink more heavily.

Heinlein was also feeling the pressure. He sometimes felt like returning to fiction, and when he mentioned this to Campbell, the editor thought that it implied that his work was either going well or “shapfu,” in which the “hap” stood for “hopelessly and permanently.” It was closer to the latter, and in the end, he didn’t do any writing at all. He developed hemorrhoids that his doctor treated with injections, leading to an abscess “in a location where I could not see but was acutely aware of it.” The Navy clearly had no intention of reactivating him, so he decided to try for the Merchant Marine, undergoing an operation to resolve his medical issues that he compared to “having your asshole cut out with an apple corer.”

He was left with “no rectum to speak of,” and he was recovering in the hospital in January 1944 when Leslyn heard from the Red Cross. Mark Hubbard was missing, but Keith and her sons were aboard the Swedish mercy ship MS Gripsholm—Leslyn had been sending money to pay for their safe passage. It took them seventy days to get from Goa to New York. After their arrival, the two boys were sent to New Jersey to live with the Campbells, where they stayed for months, until their mother had recovered. The stress led Leslyn’s weight to fall below ninety pounds, and she began sleeping for up to twelve hours a day.

From ASTOUNDING by Alec Nevala-Lee, published by Dey Street Books. Copyright © 2018 by Alec Nevala-Lee. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers. https://www.harpercollins.com/9780062571946/astounding/

Show Full Article

© Copyright 2018 Military.com. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Winners of the 2018 BookNest Fantasy Awards have been announced:

Winners of the 2018 BookNest Fantasy Awards have been announced: